EU policy-making decisions regarding the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) are influencing what we end up putting on our plates. The CAP 2023-2027 aims to be “the hammer” to carry out three key plans in the EU’s sustainability strategy: the “Farm to Fork Strategy“, the Biodiversity Strategy, and the European Green Deal. In this cycle, the CAP sets out to establish the most sustainable agricultural model to date, with a budget that accounts for up to 33% of the EU total, i.e., about 387 billion euros.

While the CAP has existed since 1962 to ensure the survival of the agricultural industry, we hoped that from this period it would also evolve to ensure its sustainability. However, in recent weeks, information has emerged about the European Commission’s intentions to reduce the established environmental requirements by almost half, which would mean a serious blow for this CAP and, in our opinion, a major setback in the European Union’s commitments to a sustainable, organic, and regenerative agri-food chain.

What changes did the CAP 2023-2027 bring under its belt?

The latest update of the EU’s Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) for 2023-2027 retains its basic structure, but brings with it important innovations in social and environmental aspects. These changes also allow EU countries to customise their national plans, thereby offering them greater adaptability to their specific challenges.

New developments in the social sphere:

Measures will be implemented to improve the labour rights and safety conditions of agricultural workers from 2025, in the quest for an effective application of EU regulations. Priority is given to supporting small and medium-sized farms, ensuring that the benefits reach active farmers. Gender equality and the promotion of youth participation in agriculture have been set as new goals. What’s more, a financial reserve of at least 450 million euros has been created to respond to future crises.

Environmental innovations:

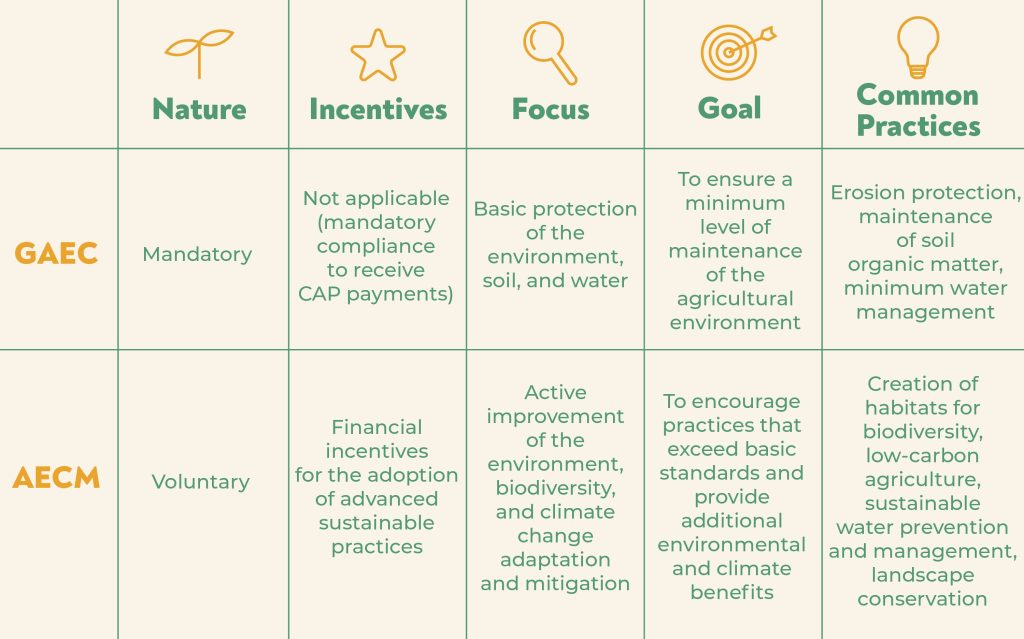

A “Green Architecture” has been introduced to incorporate the concept of eco-schemes, which are subsidies based on the adoption of Good Agricultural and Environmental Conditions (GAEC) and Agro-Environment-Climate Measures (AECM). The agricultural conditions and environmental measures both depend on National Strategic Plans, but they generally include very similar principles for all member states. The GAEC and the AECM both conform to National Strategic Plans, but they generally include very similar principles for all member states.

Eco-schemes: The new CAP currency

Eco-schemes are one of the most interesting developments of the new CAP. These are annual economic incentives offered to farmers who, voluntarily, decide to implement environmentally beneficial practices on their land. Although farmers are not required to participate in these eco-schemes, all European Union countries must offer at least one of these programmes in their CAP strategies.

Take the case of Spain, where there are nine eco-schemes tailored to the characteristics of country’s agriculture, such as support for traditional grazing and diversity in Mediterranean farms, or incentives for crop rotation and plough-free cultivation on arid lands. In the Netherlands, they have taken an even more direct course, creating an eco-scheme that allows farmers to choose between twenty-two different practices. As we can see, all this means that countries have more freedom to tailor these programmes to their specific environmental and climate needs.

However, the shift to these new systems is not going as smoothly as expected. Across Europe, fewer farmers than expected are benefiting from eco-schemes. This doesn’t necessarily mean that producers aren’t implementing pro-sustainability practices, and may instead be due to the complexity of their understanding and application. If the incentives aren’t attractive enough or if the process to access them is too complex, it’s likely that many farmers will opt out, as is already happening in several places in Europe.

A greener future at stake

In short, this CAP has brought with it important changes, but they aren’t being reflected in the real support to farmers for the creation of more sustainable and organic agriculture in Europe. As if that weren’t enough, the flexibility proposed by the European Commission based on the recent protests will likely aggravate the situation: it has been suggested to phase out the mandatory nature of certain conditions (GAEC), such as the maintenance of permanent pastures, soil cover, and the protection of wetlands and peatlands.

For example, farmers are currently required to allocate at least 4% of arable land to biodiversity to maintain full CAP subsidies, but this measure would be at risk of being phased out. What’s more, the plan is to lay up on the rules on minimum soil coverage and crop rotation, as well as to allow exceptions that would do away with practices crucial for the conservation of natural resources, such as minimum tillage, direct sowing, crop rotation, and the maintenance of areas dedicated to biodiversity.

These measures could exempt 65% of CAP beneficiaries from GAEC-related controls, which would be a setback compared to the previous period of agricultural policy, as this also failed to halt the decline in biodiversity. If this continues, this CAP could go from being, on paper, the “greenest” version to date to representing a step backwards with a possible negative impact on both biodiversity and soil health, and therefore on the long-term productivity and profitability of farms.

“The European Commission is about to dismantle conditionality requirements that are based on unequivocal scientific evidence, and which it has explicitly acknowledged as being essential tools to address current climate, environmental, and biodiversity issues”.

Meanwhile, organic farming doesn’t seem to fit into this quagmire that the CAP is becoming. Remember that the European Union, within the above-mentioned strategies, has set itself the ambitious goal that 25% of agricultural land should be farmed organically by 2030. Considering that we’re now at around 10% and that current subsidy policies aren’t supporting European farmers to become organic, we doubt that this target would be achieved, were it not for the support of initiatives such as CrowdFarming or the support of consumers. In fact, key agricultural countries such as Austria, France, Germany and Spain have decided to tighten their belts by cutting payments for organic farming compared to the previous CAP period. This decision is quite paradoxical, especially when considering the commitment to “not back down”, ensuring that the new CAP should be more beneficial for the environment and the climate than its predecessor.

Adding to this adjustment in budgets is the difficulty that farmers already certified as organic face in fitting their practices into eco-schemes, creating a sort of bureaucratic maze that complicates, rather than encourages, organic farming. For example, the “reduce pesticides” scheme excludes organic farmers simply because they have always done so. Cases like this not only hinder the progress of European organic farming, but also raise the possibility of less convinced organic farmers returning to conventional practices to receive such subsidies. Even in certain contexts, such as in France, farmers who meet less strict standards than those of the organic label often match or even exceed the payments received by them, which sends out a mixed message.

In short, it’s essential to focus the CAP towards the sustainability of the agri-food industry, and not just towards its survival. If we don’t migrate towards a more sustainable agri-food system, the cost of keeping the industry afloat will become increasingly expensive, with soils — and farmers — becoming increasingly poor. This means that we shouldn’t let up on or lower environmental standards, but instead encourage farmers’ progress towards organic and regenerative agriculture. The European Union’s ambition for more farmers to transition towards organic farming is clear, and the CAP, which accounts for a third of EU budgets, should act as a positive catalyst, never as an obstacle.

Comments

Please note that we will only respond to comments related to this blog post.