More than a month after the severe storms and floods that ravaged Valencia and much of the Spanish Mediterranean coast, the aftermath is still evident. “It will take many years to recover,” the affected farmers told us.

After the floods in Valencia, we informed you that the workers and farmers of CrowdFarming were well, although some had suffered material damage. As time has passed, we have learned about the most profound consequences that the rains and floods have had on the countryside and its socio-economic fabric. We have also witnessed the most supportive side of farmers.

Cultivating Solidarity

Ivan, from the NGO CERAI and its Horta Cuina initiative, has been coordinating small local farmers for some time – mostly organic – to provide organic fruit and vegetables to Valencian schools. This group of farmers supplies vegetables for the monthly CrowdFarming subscription.

Thanks to the good coordination they already had in place, this group of farmers was able to quickly get down to work. Farmers who suddenly saw their demand reduced – the economy is paused in these situations – took their products to communities that needed it – the shops in the area had been destroyed. The operation was financed with donations received by several organizations for the “Cultivate Solidarity” initiative, thanks to which farmers received payment for their produce, while the affected communities received the product at no cost. The NGOs that participate in the initiative are clear about it, when the businesses start operating again, they will take a step back. Solidarity cannot – should not – compete against local commerce.

We went to visit one of the member farmers of Horta Cuina: Bruno. Bruno has lost 40% of his production; his potatoes, sweet potatoes, tomatoes, cabbages and lettuce were submerged underwater and ended up rotting. Seeing his impeccable-looking aubergines, he tells us that the plant has actually absorbed so much water that, if they were harvested, brown spots would begin to appear caused by the excess water and the aubergines would end up rotting before reaching the consumer. Beyond the losses recorded by Bruno (€50,000), it is the long-term consequences that most concern this group of organic producers. Where did this water and sludge come from? What did they carry? Could they have contaminated their soils? Could they, then, lose organic certification? At the moment, they are carrying out soil analyses to have a first reading of the situation.

Up to a quarter of this group of producers has been affected in a similar way to Bruno. While acknowledging the devastation that the water has caused in their fields, he appreciated the role they have played in alleviating an even greater misfortune in residential areas. “The crops have slowed down the water, if it had been all asphalt accelerating the speed of the water, I don’t want to think how this would have ended.”

Saving the soil

The role of agricultural advisors is fundamental when it comes to a transition to another way of doing agriculture. Someone who earns the trust and respect of the farmer has the key in their hand to make a big impact. This is the case of Juan, an agricultural advisor to organic and conventional farmers, and a great believer in regenerative agriculture, which is why we met. Juan met us in Valencia to show us some of the fields most affected by the storms and floods.

We spent hours with Juan and one of the farmers he advises, Enrique, seeing farms covered by reeds, mud, and all kinds of debris and garbage dragged by the flood. Enrique practices conventional agriculture, but there is no doubt that, after witnessing the impact that water can have, he will plant vegetation cover on his farm. Enrique told us that “the water, as it finds a crack through which to sneak, destroys you” and he explained to us excitedly how by having the ground covered, he will be able to stop the water and prevent it from taking all his soil ahead.

In the regenerative agriculture group where we met Juan, many farmers send comparisons of their farms, in which they implement regenerative practices, and those of their neighbors. It is impressive to see how the regenerative farms have been able to absorb and filter water, conserving their soil, while across the border you can see floods of water and mud, dragging the soil that is so hard to create. Regenerative practices such as vegetation coverings or a design that allows water to be stored and conducted are some of the techniques for dealing with torrential rains and their antonym – droughts. “I’ve also noticed that, despite three years of drought, we’ve spent less on irrigation and inputs, yielding more kilos. It has taken years, but a life and more generations await us,” said Gonzalo, producer of the organic oil”Olioli” in Requena, Valencia.

La Junquera, one of our farmers, also reported through their social networks that, despite the fact that so much water didn’t fall in their area, they coped well with the storm thanks to the regenerative techniques they already implemented years ago. They also said that improvements they plan to carry out to deal even better with future downpours: “We need to make our water management structures larger and more resilient to face extreme weather events more frequently. Regenerative agriculture, which includes water management structures, cover crops, vegetation strips, hedges and the improvement of soil health, is key to reducing water speed and increasing soil absorption capacity.”

With an increase of just 1% in organic matter in the soil, it can retain up to an additional 75,700 litres of water per hectare. This sponge effect, especially beneficial during heavy rains, significantly decreases the amount of water that runs on the surface, thus reducing run-off, erosion and waterlogging. In addition, by controlling the volume and speed of water flowing into rivers, the risk of flooding in nearby communities is minimized.

However, little can be done when “a tsunami that drags mud, reeds and debris” arrives, as described by some interviewees. Juan and Enrique agree that help is now needed in the so-called “ground zero” of the disaster, where the priority is for people to return to their homes. But they hope that, after cleaning up those areas, they will come and help the farmers. Many still cannot access their farms even to see the state they are in, since “it is necessary to repair roads, clean and remove the mud to prevent the trees and their roots from rotting, as the soil cannot breathe.” Many try to quantify the magnitude of the disaster (AVA-Asaja, the association of Valencian farmers, estimates 1,089 million), but it is still difficult to know the real medium- and long-term consequences for these soils and the crops that grow on them.

The hero of the tractor

Vincent, from Hort de Zéfir, has been selling his mandarins through CrowdFarming since its inception. His neighboring farm, Naranjas del Carmen, is the farm of CrowdFarming’s founders, Gonzalo and Gabriel Úrculo. Vicent, driven by them, set out to make the leap to organic farming. He acknowledges that it hasn’t been an easy road, but he doesn’t regret it. Now his job is much more rewarding, and he keeps discovering every day how to do it better.

We drove with Vicent from his farm in Bétera, Valencia, to the town of Picanya, where the students of the Gavina School welcomed him as a hero and handed him a letter that said “thank you for helping us return to school”. During the weeks that separated the floods from the reopening of the school, Vicent traveled for up to 3 hours with his tractor to clear the mud from this school that his children went to years ago.

Vicent is part of a collective of organic farmers led by Nando Durá. When we got to see Nando, he had just been on TV explaining the situation. Nando has been responsible for coordinating the help of many farmers who put their machinery at the service of the most affected areas. “We cannot stand still when we are most needed, we did it by disinfecting the streets during the confinement of COVID-19, and we do it now with floods.”

If there is something positive that Nando brings out of all this, it is the visibility that the producer is gaining. Nando has his own website where he sells his citrus fruits and rice and, according to him, people are surprised to meet farmers and discover that they can buy their product directly from them through the internet and without intermediaries.

In southern Spain it also rains

Two weeks after the storms and floods that ravaged Valencia, it was time, again, for the southern part of the peninsula. The Axarquia area of Malaga, where many of our subtropical and citrus farmers are located, was especially affected. Before, we talked about the need for vegetation coverings to deal with torrential rains. Just those days, there was a course organized by CrowdFarming with farmers from the Axarquía on vegetation coverings, which we had to postpone due to the red warnings of storms and floods.

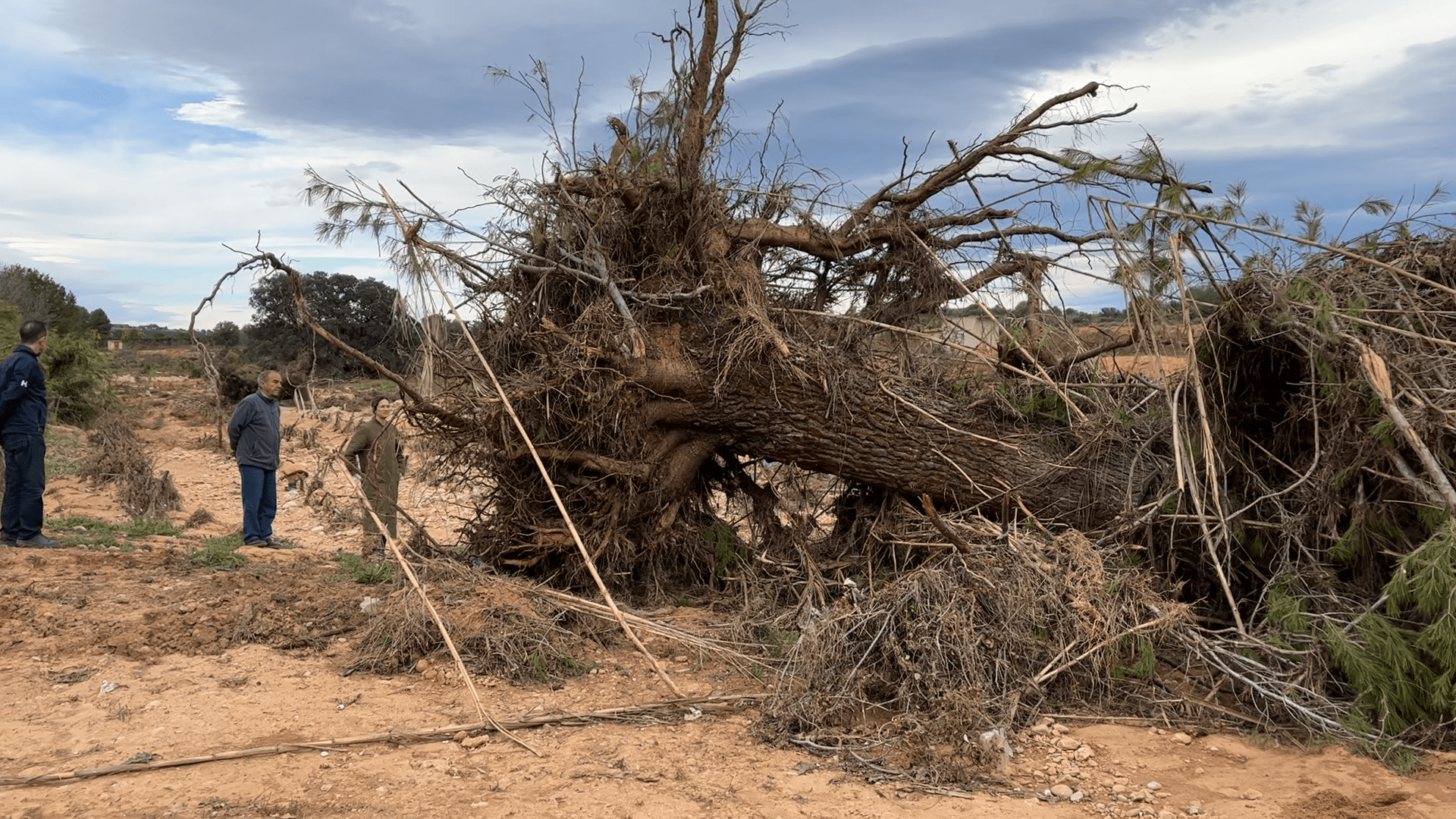

Jessica, from Finca Aguilar, shows us how the lemon trees planted by her grandfather have turned upside down with the force of the water. We can see their roots looking up at the sky. Jessica acknowledges that “fortunately, thanks to the protocol adopted after what happened in Valencia, only material but not personal damage has occurred.” In the Axarquia, something similar happened as in Valencia, “the large amount of rainfall accumulated both in the town itself and in the upper areas of the province, have caused the flow of the river to rise suddenly, flooding and dragging everything in its path,” continues Jessica.

In the why’s everyone finds their own culprits. Jessica, like other farmers, tells us about the reeds that clogged the waterways. Others talk about dams, government, climate change or urban planning. What everyone is clear about is one thing — they’ve never seen this before: “the water reached more than six meters in height,” Jessica tells us, “something completely incredible, we’ve been growing citrus fruits in these orchards for more than 50 years and my parents, grandparents or great-grandparents have never seen anything like it.”

It’s more than just a material loss, Jessica explains. “We’ve lost a large part of our farm, which we’ve been working on for more than three generations,” but she doesn’t lose the desire to continue working for her family’s legacy. “With hard work and effort, we’ll bring colour to this great disaster.”

DANA: The older sister of the “Cold Drop”?

Anyone who knows the Spanish Mediterranean coast well has heard of the torrential rains called “cold drop”, typical of the months of September and October. This phenomenon occurs when an isolated polar air mass begins to circulate at very high altitudes and collides with the warmer and more humid air typical of the Mediterranean at the end of the summer, often triggering storms that discharge a large amount of water in a short time. In other words, a cold drop is a DANA, “Isolated Depression in High Levels”, the same that has caused havoc on the Spanish Mediterranean coast during these weeks. What has made it so devastating this time, then?

Experts have long warned that extreme events will become more frequent and intense. The IPCC (a UN scientific body that assesses climate change), announced in its latest report that Europe would face an increase in climate risks, including the risk of floods, which would affect people, economies and infrastructure, and losses in crop production due to combined heat and drought conditions and extreme weather events. A preliminary report by the academic organization World Weather Attribution has established that global warming made the rains that fell on Spain 12% more intense and doubled the chances of them occurring

In the world of agriculture — especially ecological and regenerative agriculture — we are used to hearing about “increasingly frequent extreme weather events” and their possible impact on our food security. It is part of our daily life to talk about droughts, harvests damaged by untimely hail or degraded soils. But on October 29, 2024 and the days that followed, Valencia and much of the Spanish Mediterranean coast were brutally shaken, and its consequences reverberated throughout the world.

The signs were, both that these extreme events would come and what the flood zones were, however, no one had prepared for something like this. Let’s learn from what happened, to change reactivity for resilience: a long-term race more than a sprint. The IPCC also proposes how to cope with these changes, and some closely resemble our vision of what agriculture should be: “Conservation, improved management and restoration of ecosystems, including the protection and restoration of biodiversity, can help strengthen resilience to climate change and provide a wide range of co-benefits, including support for livelihoods, human health and well-being, food and water security, and disaster risk reduction.

Comments

Please note that we will only respond to comments related to this blog post.