Assessing the impact of the lifecycle of an orange

Climate change – largely affected by greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions – is a reality that threatens both communities and vulnerable sectors around the world. Among these, one of the most affected is none other than the agricultural sector and, with it, food security at global, regional and national levels.

Food production accounts for more than a quarter of global greenhouse gas emissions. While it is inevitable that we will produce this food for consumption, it is always possible to do so in a more sustainable and environmentally friendly way. If, as consumers, we want to contribute to the adoption of this type of model, we need viable, accessible and transparent purchasing alternatives in terms of the impact that our decisions are generating.

With the intention of offering this alternative to CrowdFarmers – not only a fairer and more sustainable purchasing alternative, but also one that puts its impact into numbers – during 2022 we decided to conduct a study to quantify the real impact of the CrowdFarming model in terms of carbon footprint and food waste. The study took into account the journey of the orange from farm production to the consumer’s home, comparing it to the supermarket organic food supply chain. For this, we started, of course, with one of our flagship products and the one that started it all: oranges.

By choosing organic products with a lower carbon footprint and less food waste, consumers – CrowdFarmers – become an active part of the shift towards a fairer and more sustainable agri-food chain. However, this does not mean that all the results are favourable for CrowdFarming. This study has also helped us to identify where we have room for improvement and to get down to work.

The study

For this initiative, the services of the specialised consultancy Hands On Impact were used to conduct the study and model the journey of 1 kg of oranges produced in Valencia (Spain) until they reach the customer’s home in Berlin (Germany).

To measure the impact of CrowdFarming, two categories were taken into account: at the environmental level – with the carbon footprint as the main indicator in kg of CO₂ emitted -, and food waste – expressed in kg of food wasted.

The scenarios

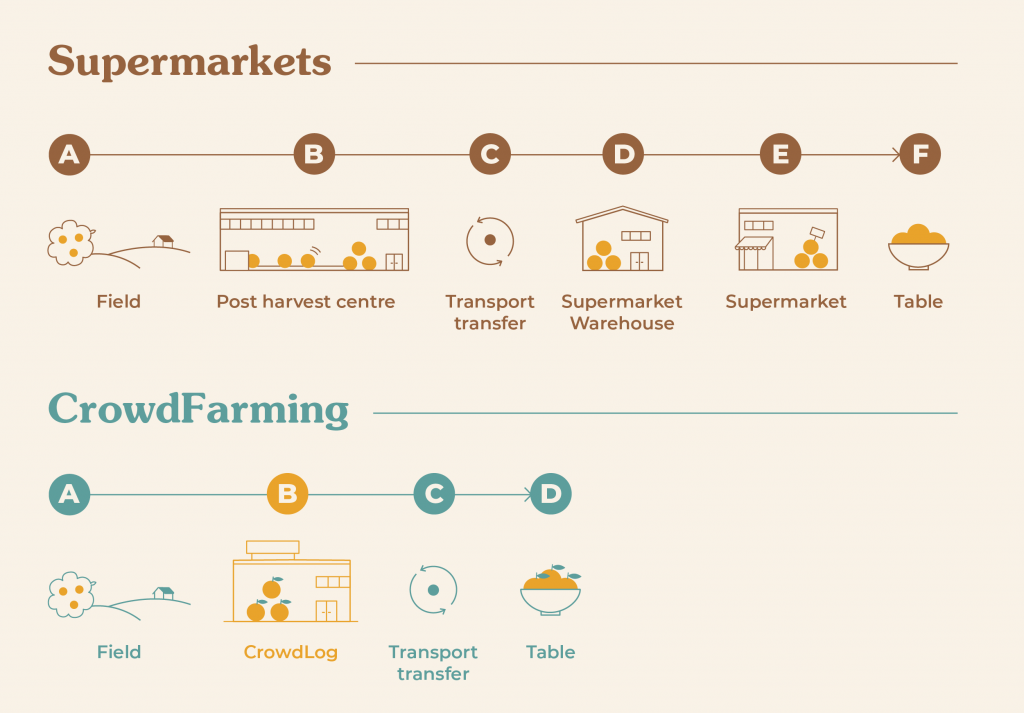

We considered two scenarios, along with their impact categories and stages (Figure 1): the CrowdFarming scenario and the supermarket scenario.

Supermarket Scenario

The first step is a standard organic farm, for which data from scientific studies were taken as a reference, contrasted with other data from professional organic production associations (Ecovalia, 2022).

After harvesting, in this scenario, the oranges from the farm are transported to the post-harvest centre, where the product can remain artificially preserved for 4 days to 2 months, depending on the studies consulted. However, for this model, only a period of 15 days of storage in refrigerated chambers has been taken into account.

From the post-harvest centre and after a change of transport in Frankfurt (Germany) to smaller vehicles, the product is distributed to the warehouses of the supermarket, in this case studied, located in Berlin. The journey comes to an end when the consumer goes to the supermarket to do the shopping and the oranges arrive at home.

CrowdFarming Scenario

The starting point is a standard organic farm, so the same cultivation model is used as in the case of the supermarket. After the cultivation phase in the field, the preparation of the order takes place in CrowdLog*, our logistics centre in Valencia (Spain). The transport consists of the transfer of the oranges from the farm to CrowdLog, the export to Germany up to the transport exchange point in Speyer, from where the products are delivered to the final destination, in this case to the CrowdFarmer’s (consumer’s) home in Berlin.

In the case of CrowdFarming, the harvesting process and the journey of the produce to the CrowdFarmer’s home begins only when a CrowdFarmer places an order. The farmer selling in CrowdFarming harvests on demand, which means that the oranges in CrowdFarming wait on the tree – not in cold storage. In this way, a CrowdFarming product will take on average 5.5 days to reach your home from the tree, in contrast to the supermarket model, where oranges can spend up to 2 months in cold storage.

In the case of supermarkets, we would also have to add the time it takes for the product to travel from Valencia to Berlin and the waiting time in other stores and supermarket shelves.

*Only farms close to the region of CrowdLog go through this logistic centre. For more information on CrowdLog please refer to our 2022 Impact Report.

Carbon footprint

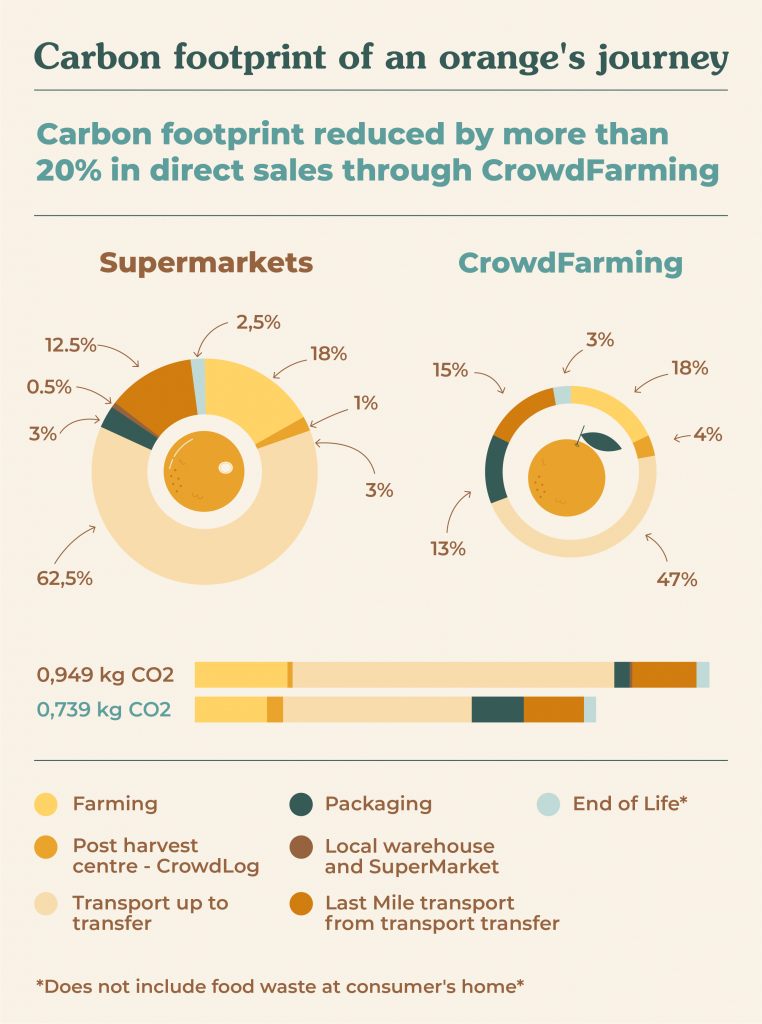

The carbon footprint (Figure 2) refers to the amount of greenhouse gases emitted during the production and distribution of a product, and is a key indicator of a company’s environmental impact.

We can see that the CO₂ emissions data for CrowdFarming equates to 0.74 kg CO₂ emitted throughout the entire supply chain; 22% less than the 0.95 kg CO₂ emitted in the supermarket supply chain.

In both cases, transport accounts for more than half of the total emissions, followed by agriculture, with packaging close behind in the CrowdFarming scenario alone. Let’s focus on what happens at these three stages and how the two scenarios compare.

Farming

For the comparison, we have used in both cases the average carbon footprint of 1 kg of organic oranges grown in Valencia, being as conservative as possible in the comparison. However, we have investigated the carbon footprint of the production phase on one of the farms selling through CrowdFarming. Emissions in this case were considerably lower than average: 0.04 kg CO₂ per kg of oranges compared to 0.14 kg CO₂ per kg of oranges on an average organic farm. This can be related to two main factors, the lower amount of inputs used in the case of the CrowdFarming farm and a higher than average production per hectare.

The productivity of the CrowdFarming farm studied is 30 tonnes per hectare, while other studies report a productivity of 22-24 tonnes per hectare.

This increase in productivity in the case of the farm studied with CrowdFarming may be due to certain dynamics that are avoided thanks to the direct sale model. CrowdFarming avoids situations such as low farm-gate prices (those paid to the farmer) or large fluctuations in demand, which can cause farmers to leave part of their crops unharvested. This unharvested fruit is not counted as food waste and is only reflected in a decrease in the total volume of production.

Although the results obtained on the CrowdFarming farm where data were collected were very good – or precisely because of that – it was decided to use data from a standard organic farm as a model in the study in both scenarios. In this way, it is avoided to assume that the rest of the CrowdFarming farmers’ farms have the same specific conditions. Furthermore, by using data from a standard organic farm in both scenarios, the differences between the supermarket and CrowdFarming supply chain can be measured more accurately, without allowing the type of crop to influence the results.

Transport from farm to table

Transport – including the last mile – is the factor that most influences the carbon footprint of oranges, accounting for around 70% of the total footprint. This is mainly due to the long distances that Valencian oranges travel to Berlin.

Although transport is a relevant factor in both scenarios, we have found that CrowdFarming’s efficiency efforts result in a 22% reduction of the emissions produced compared to the supermarket model. This reduction in emissions is directly related to both the high occupancy of the trucks responsible for transporting the produce – which travelled on average at 93% of their capacity during 2022 – and the reduction in food waste during the supply chain. The food waste we see in the supermarket scenario translates into more resources being used to produce and transport oranges that will end up in the trash.

In addition to these factors that we have taken into account for the efficiency of the CrowdFarming model, additional initiatives are undertaken to reduce the carbon footprint of our shipments. Firstly, companies such as Trucksters allow for constant movement of produce through driver relays, which significantly reduces the time the oranges remain refrigerated in the trucks that transport them. Last mile carriers are also being sought that offer sustainable alternatives, such as electric delivery. Finally, and as a last resort, an extra price is paid to offset the carbon footprint. In total, 65% of CrowdFarming’s last mile shipments are offset. However, this additional reduction and these compensation measures are not included in our calculations of the journey of 1 kg of oranges.

Packaging

In the case of the supermarket supply chain, only packaging used to ship large volumes of product to the supermarket has been taken into account, and not packaging used to sell the product to the consumer. We are referring to packaging that can be seen on supermarket shelves, such as plastic nets or citrus bags – which could increase the carbon footprint by more than 8%.

We also wanted to be conservative when calculating the carbon footprint of the packaging used by CrowdFarming by considering one of the least efficient formats offered by our model – 5 kg instead of 10 or 15 kg formats – as transporting smaller volumes increases the ratio of packaging used per kilo of product.

In addition, CrowdFarming encourages farmers to avoid the use of plastics for packaging produce, except in cases where food safety is compromised. In the case of oranges, only compostable materials, i.e. cardboard, are used.

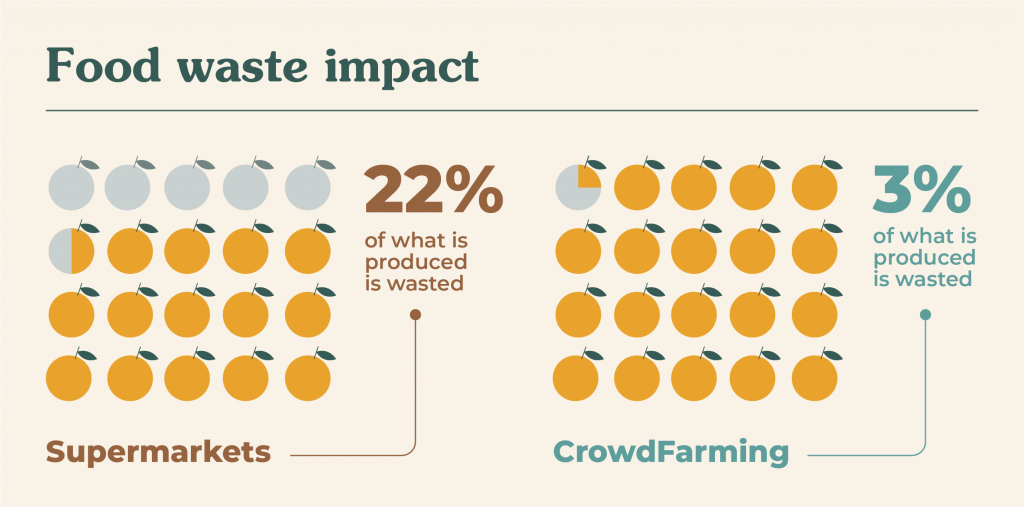

Food waste

Food waste is a significant contributor to climate change, accounting for approximately 8-10% of global greenhouse gas emissions, equivalent to the emissions generated by the entire transport sector.

We have found that, in the supermarket supply chain, for every 100 kg that reaches consumers’ homes, 30 more are produced and wasted before reaching their final destination. In contrast, in the CrowdFarming scenario, less than 3 kg of oranges would be wasted due to food safety issues (e.g. rotten produce) for every 100 kg that reach consumers’ homes.

When food is wasted, all the resources used to produce it are also wasted, including water, energy, land and fertilisers. In addition, the resulting waste generates large amounts of greenhouse gases when it decomposes in landfills, even more so when it is food waste. Since we are focusing on the environmental impact, we will not go into the enormous social and economic impact of global food waste, although one can imagine that this issue is immensely relevant if we are to create a supply chain that is not only sustainable, but also fair.

This study has served to test the hypothesis on which much of the CrowdFarming model is based: we present an alternative to the way things are traditionally done in supermarkets, reducing food waste and carbon footprint. It has also served to focus our attention on those aspects we need to improve: supporting farmers to go beyond organic, finding alternative forms of transport and packaging, and making consumers aware of the impact of each of their actions. Finally, we believe that this experience has further increased our thirst for knowledge, transparency and self-criticism.

Comments

Please note that we will only respond to comments related to this blog post.